In 1953, when I was eleven years

old, I left my mother, my childhood, innocence and my village behind and went

to do my high school studies in Dhenkanal town and with that, I graduated from listening

to ghost stories and being dead scared of darkness and the frightening spirits

of darkness to reading detective novels and enjoying them. In my village I had

never heard of detective stories. Those days for school students, reading

anything other than the prescribed text books was considered bad by at least

the lower middle class families; forget about detective stories, even newspapers

were taboo for me. I didn’t feel the need for newspapers then; the only news

that interested me was about the football matches played in Cuttack, which was

the capital of Odisha then. A owner of a grocery shop near our school was

generous enough to allow me to read the daily paper named “The Samaj”. Whatever

was considered worthwhile for us to know about the world outside our school, was

given to us in our classrooms: names of our President, Vice-President, Prime

Minister, Chief Minister of our State, our Education Minister, Director of

Public Instruction, etc. Like the few

classmates of mine, who wanted to experience the forbidden pleasure of reading

detective books, I had to find ways of hiding the detective book I was reading

from my teachers and my uncle at home. Once in the Mathematics – of all

subjects! – Class, I was caught reading a detective novel. I had done this quite

a few times in the class even when teaching was going on, but it was very

risky. More than once I was caught and my teacher would make me stand on the

bench with one hand up. For a more serious offence one had to stand on the

bench with both hands up, reminiscent of the kirtan posture associated with Sri

Chaitanya’s sect. Padmanabha Rath was a good teacher; he was as good at

mathematics as at devising ways to punish us.

I cannot recall the names of those

books. As for their authors, we, who had a passion for detective novels, never

bothered about them. What mattered was the story. For us, all detective novels

were interesting; it was only a question of degree: some were more interesting,

some far more interesting, etc. It was only after reading dozens and dozens of

such books that I felt some were not really all that interesting; however, all

the same I did not fail to read even those; but I did not read those on payment.

The dacoits did not scare me all that much; partly because those thugs weren’t

ghosts, who we had never seen but were people like anyone on the streets,

despite their black gowns with silly hoods and ugly masks. But there was another

and weightier reason. I couldn’t afford to be scared because at home a

detective book could be read when, if it was day time, there was no one there,

which wasn’t very often the case or at late night, when my uncle would be on

night duty, which was often the case, and my aunt and “cousin sister” (no

apologies for using an “Indian English” expression) would be already asleep in

the same room. I would light an oil lamp and go to another corner of the room

to relish the doing of the dacoits and then of the private detective. In our

detective novels, the private detectives turned out to be much smarter than the

police. There was no explicit mention in the books as to whether they earned

more money doing private investigation than those who were in the police

department, with secured salary and pension. But we were never curious about

the lives of those characters outside their job life.

Sometimes one had the urge for reading

some particular book about which one had heard so much. Then one had to pay.

Many times I paid two paisa (a rupee was sixty four paise) for such a book for

a day. That was quite some money then. The day I borrowed a book, I had to

forego part of my mid-day snack. But the prospect of mental enjoyment more than

compensated for the half-satiated hunger.

The first detective book I read

was about dasyu (dacoit) rabin (Rabin)

and his younger brother dasyu rattan (Ratan).

There was a beautiful princess there in the story who the senapati (army chief) of that small kingdom wanted to marry. He was

already married, but had kept everyone in the dark about it. Not being a king,

he couldn’t marry more than once. To marry the princess, he had the consent of

the king, who was weak and dependent on him for his throne. The helpless

princess somehow managed to get in touch with Rabin and Ratan, who she called “brother”

and these two not only saved her from that marriage but also exposed the senapati, humiliated him and put him

squarely in his place. The good dasyus

became my heroes instantly. They were not only good, but very intelligent. What

impressed me most was that they would announce in advance that they would be at

such and such place and would be there and do what they wanted to do and escape,

no matter how many policemen or soldiers were in duty to arrest them. I read

that book many times.

Unlike Rabin and Ratan, the

dacoits in the books I read thereafter were crooks and criminals – each one of

them. There was this book called “Denjer

Signal (Danger Signal)”. That was what the thug called himself. He was a

ruthless murderer, who always managed to escape after murdering his victim. May

be the novel I have in mind was one of a series - Denger Signal series? Except for Rabin and Ratan, I do not recall

there to be any detective story in which the rogue was not eventually caught.

But it was never the police who caught them. They were always outwitted by the

criminals. It was always the private detective who got them - he always had a

friend who was his assistant in investigation, like Sherlock Holmes had his Dr.

Watson. The police came only at the very end with the handcuffs. Denjer Signal attracted me probably

because I was fascinated then by trains and train signals.

These novels introduced me to the

life of the rich, who were not royals. Generally speaking, in these novels only

the criminals enjoyed a rich life style. I never read a detective novel or a

story where the criminal walked to his destination or rode a man-pulled

rickshaw or a cycle rickshaw, as we, the commoners did. He rode for free; the rickshaw

wallah did not have the courage to ask him for money. I encountered many words

before I saw what they referred to: the crooks who behaved as law-abiding men during

the day and killed at night sat on sofas which I had never seen. I knew the

word “sofa” before I saw the object called “sofa”. But it was the food that

they ate that fascinated me. They would have anda bhaja (egg fry, i.e., omelette), mansa chap (mutton chop), kalija

bhaja (liver fry), kukuda jhola

(chicken curry), cakes and biscuits. I had tasted none of them, except

biscuits, but those I had eaten were pathetically different. As for eggs, I

knew the taste of only the boiled egg. In my childhood days it was sick food

for me. In the novel, I would re-read the lines containing these food names

again and again. They were remote, vague and alluring. When at 15, I went to

Cuttack for my college education in Ravenshaw College, I had my first anda bhaja and mansa chap – at the best restaurant for these foods those days:

Khan Hotel. Today I cannot say which I relished more: the food words, which I

would roll and roll and chew in my mouth or the delicious stuff that I had at

Khan Hotel. Before I leave this topic, I must mention that Rabin and Ratan were

described eating just biscuits dipping them in a cup of tea. They were

vegetarians.

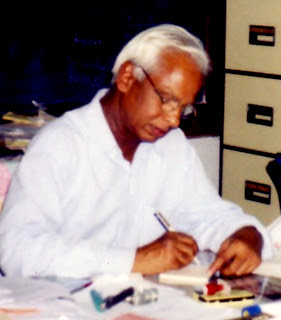

I cannot recall when I began to read Kanduri Charan Das’s detective novels. For the first time, the name of the author mattered to me. At A.H. Wheelers in Cuttack or Puri or Kharagpur railway station I would look for Kanduri Babu’s novels. I must have read almost all his novels. These were intelligent novels where the focus was on investigation. In his novels, it was not the criminal, but the detective, who was the hero of the story. The memory of one of his stories lingers in me still. It was the deeply touching tragic story of Sadakat, a good man who had killed a criminal in order to avenge the killing of the girl he loved. The criminal was a “king”. Sadakat was found and was arrested, but I hoped for once that the author had planned a different ending! Now, more than five decades after I read Sadakat’s story, I still feel very sad about Sadakat.